Cover Story - Solving the Gangrenous Dermatitis PuzzlePreventing late coccidiosis cycling with vaccination may halt this costly bacterial diseaseIf you’re like many other modern poultry operations, you probably vaccinate at least a portion of your broiler chicks for coccidiosis. Maybe you do it to improve the performance of broiler flocks when traditional infeed anticoccidials don’t seem to hold up to the challenge. Or maybe you do it to meet the growing consumer demand for birds raised without drugs. Now, early field trials and experience indicate there’s one more reason to vaccinate for coccidiosis: It can help control or eliminate the growing problem of gangrenous dermatitis.

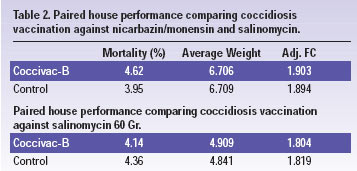

The consequences of gangrenous dermatitis include high mortality, carcass condemnations and trimmed parts. Economic losses are an estimated $0.80 to $1.31 per affected bird, which is significant because the disease occurs late during grow-out, when a lot has already been invested in birds that can’t be saved, investigators say.1 Number one health problem “We’re hearing more people discuss this disease,” says Dr. Charles Broussard, global technical services director for Schering-Plough Animal Health’s Poultry Business Unit. At some U.S. poultry companies, gangrenous dermatitis has become a very serious problem, with 10% to 25% of flocks affected and mortality running about 2% to 4% — and sometimes higher. The incidence seems severe enough that it’s on the minds of veterinarians and has become a “number one” health problem for some producers, he says. Broussard notes that when 17 U.S. broiler company veterinarians were asked in a survey to list their top disease concerns, 12 cited gangrenous dermatitis. It was, in fact, “the most consistent and serious problem in their operations,” according to a 2005 Report of the Committee on Transmissible Disease of Poultry and other Avian Species. It has long been thought that gangrenous dermatitis starts with a scratch that gets infected with a bacterium, which rapidly proliferates when birds also happen to be immunosuppressed due to diseases such as infectious bursal disease (IBD) or chick anemia virus (CAV). The remedy was thought to be good control of IBD, CAV and other immunosuppressive diseases, as well as management changes ranging from low lighting to special diets that are primarily aimed at keeping birds calm to prevent scratching. But control of IBD, CAV and the environment has not resolved the problem of gangrenous dermatitis, says Broussard. In addition, recent experience and trials indicate that an instigator of gangrenous dermatitis may be one not considered before, and that’s late coccidiosis cycling. “The remedy may be coccidiosis control that prevents late coccidiosis cycling — and there may be no need to make significant management changes,” he says. Adds Broussard: “Coccidiosis might have been a cause of dermatitis all along, but we’re approaching coccidiosis control differently now. We aren’t using as many anticoccidials and resistance has developed to some of them, which may be allowing dermatitis to rear its head.” Patterns of disease Although high mortality is the most obvious sign of a gangrenous dermatitis outbreak, says Broussard, producers might also notice that affected birds have a poor appetite, poor coordination and leg weakness, skin lesions and edema. The pathogen most often associated with gangrenous dermatitis is clostridium of various species, but Escherichia coli and staph infections can also be the culprits. The pathogens act as an opportunistic infection, which is set off by coccidiosis.  “Even though spring is often associated with outbreaks of dermatitis, lately we’ve also seem problems with the disease occurring in winter. Cold weather is a stress in and of itself, but that’s also the same time that a lot of flocks experience a late coccidiosis challenge due to the anticoccidial control program in use,” he says. “The disease is occurring in birds on chemical-to-ionophore programs and on straight ionophore programs,” he adds. Broussard points to research conducted by Dr. Steve Collett of the Poultry Diagnostic and Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens, which was presented at the Georgia Veterinary Medical Association 2006 annual meeting. The results diverge from standard gangrenous dermatitis dogma. Collett’s challenge model consistently induces gangrenous dermatitis lesions in 100% of challenged birds and the degree of mortality is dose-responsive. Most immune-competent broilers are able to contain the infection — become culture negative 7 days after challenge — and recover. Current dogma regarding the pathogenesis of gangrenous dermatitis is based on the premise that when the skin’s barrier function is compromised by scratches, contamination with Clostridium perfringens commonly occurs and the progression of disease following wound contamination requires the bird to be immune-suppressed. Using his model, Collett demonstrated that immunosuppression caused by IBD and CAV did not increase the severity of gangrenous dermatitis lesions. From this, he suggested that immunosuppression is more likely a predisposition to the process of infection (currently thought to be skin scratches) and not the consequence of infection (skin necrosis). This is important because it supports Collett’s earlier hypothesis that the skin and scratches is not always the way that clostridial organisms enter the body and cause gangrenous dermatitis; an alternative route is mostly likely the gastrointestinal tract. Collett went on to point out that, in the field, gangrenous dermatitis typically occurs in 4- to 6-week-old broilers. This coincides with the time between peak coccidiosis challenge — peak oocyst output is around 28 days of age — and the development of solid immunity against Eimeria spp. challenge at 6 weeks of age. Gut lesions caused by  Eimeria parasites, particularly late cycling Eimeria maxima, could easily provide a portal of entry for the clostridial organisms responsible for gangrenous dermatitis, as evidenced by human research on the pathogenesis of gas gangrene. Interestingly, the prevalence of gangrenous dermatitis in flocks vaccinated with Coccivac appears to be extremely low when compared to vaccinated flocks. It would seem that reducing the severity of gut epithelial damage, or shifting the time at which it occurs, could be an important means of preventing or at least reducing the prevalence of gangrenous dermatitis. Major producer’s experience Consider the experience at one large US broiler producer, where gangrenous dermatitis became a problem in several complexes, particularly among small birds that had received nicarbazin/ monensin for coccidiosis control. “We had dermatitis coming in at 32 to 35 days — toward the end of the anticoccidial control program cycle,” says the producer’s veterinarian, who spoke to CocciForum with the condition that his company not be revealed. “Gangrenous dermatitis can be devastating and, for some operations, results in mortality as high as 8% per week. That’s very costly to individual growers,” the veterinarian says. The producer followed the problem for a while and realized that “we had some late-breaking coccidiosis,” he says. When the birds received the chemical anticoccidial Clinacox after nicarbazin/monensin, the dermatitis stopped. The veterinarian has not been able to link gangrenous dermatitis outbreaks with the traditional villains IBD nor  CAV. “We’ve had dermatitis in areas with a good IBD program and in birds that I think are normal. We have also had dermatitis in chickens vaccinated against CAV. The only link I’ve seen is this late coccidiosis challenge.” Some complexes with larger birds on the same nicarbazin/monensin program also experienced gangrenous dermatitis, which ceased when coccidiosis control was managed with vaccination administered at the hatchery to initiate early immunity and prevent a late coccidiosis challenge. “I don’t want to sound too definitive about the association, but we see much less dermatitis when we control coccidiosis late in the production cycle,” he says. “I think the vaccine helped with dermatitis because it did away with the late coccidiosis challenge.” Based on his experience, this poultry veterinarian believes that the observed link between late coccidiosis cycling and gangrenous dermatitis represents a changing pattern. He also thinks there may be a breed predisposition. Gangrenous dermatitis has occurred in three different bird breeds, but there have also been breeds that seem highly resistant to dermatitis, he notes. Integrator’s trial To test the theory that gangrenous dermatitis may be triggered by a gut insult created by the late coccidiosis cycling that results with traditional in-feed anticoccidial programs, another large broiler integrator conducted a trial. In January 2006, four farms of straight run broilers were immunized with one dose of the coccidiosis vaccine Coccivac-B, which was sprayed on at one day of age in the hatchery before chicks were placed on farms with the strongest history of gangrenous dermatitis. All other management and vaccination procedures were identical to the standard company program. The trial was then replicated with the same format in April 2006 for the next sequential grow-out on the same farms and houses. On three of the farms, two cycles of Coccivac-B vaccine were administered in the spring, a peak time for gangrenous dermatitis outbreaks. During the same time period in 2005 — when coccidiosis control comprised one cycle of nicarbazin/monensin then a cycle of salinomycin — average mortality exceeded 10%, but after coccidiosis vaccination in 2006, mortality was only about 3% (see Table 1). The “sister” farms of the trial houses had gangrenous dermatitis and a mortality of 3 to 6 birds/1,000 per day for at least 4 days. At the fourth farm in the trial, paired house performance was studied; coccidiosis vaccination was compared against nicarbazin/monensin and against salinomycin (Table 2). Performance in vaccinated birds was very similar or better to performance among birds receiving traditional anticoccidial control, according to the results. For instance, the average weight in birds that received Coccivac- B vaccine was 4.9 lbs, compared to 4.8 in birds receiving salinomycin. Says Broussard, “These trial results confirm our anecdotal observations that the prevailing trigger for dermatitis can be correlated to late coccidiosis cycling. Traditional anticoccidial programs that shift coccidiosis cycling into peak dermatitis periods may compound the effect or even create it. “Coccidiosis vaccination shifts coccidiosis cycling out of the dermatitis ‘window’ to eliminate what now appears to be the predominant predisposing factor for dermatitis,” he says. (See Figure 1). In addition, control of gangrenous dermatitis by preventing a late coccidiosis challenge has not required management changes traditionally necessary to rid an operation of this disease, Broussard says. Vaccine is cost competitive Economic data from the trial was also considered as well as data from other sources. Compared to other methods of anticoccidial control in the trial, Coccivac-B was less costly for controlling coccidiosis. This was the case even before other benefits of vaccination, such as reduced mortality and fewer medication costs, were considered, he says. “Most exciting is the ability to reduce or eliminate dermatitis by shifting coccidiosis cycling, which gives coccidiosis vaccination added value,” Broussard says. “We’re on to something here that could really help broiler producers get rid of the dermatitis problem, the staggering losses caused by this disease and, at the same time, provide good coccidiosis control,” he says. Reference 1 Norton, RA et al. Gangrenous dermatitis reemerges in broilers. Watt Poultry USA. March: 38. Source: CocciForum Issue No.12, Schering-Plough Animal Health. |

© 2000 - 2021. Global Ag MediaNinguna parte de este sitio puede ser reproducida sin previa autorización.

© 2000 - 2021. Global Ag MediaNinguna parte de este sitio puede ser reproducida sin previa autorización.