Energy Conservation

New research-driven insights on how chickens utilize

feedstuffs can help broiler producers develop new strategies

for getting the biggest bang from nutritional programs

while improving flock health.

Some of those insights were the focus

of a presentation delivered by poultry

nutritionist and researcher Dr. Robert

Teeter, a professor and nutritionist sat

Oklahoma State University, at a

recent CocciForum symposium in

Florianopolis, Brazil.

Teeter pointed out that energy obtained

from feed is used to maintain tissue

and organs, regulate body temperature,

develop immunity and support various

physical activities, including acquiring

more food to support the growth curve.

After those essential needs have been

satisfied, whatever energy that remains is

devoted to growth—or at least that's the way it's supposed to work in a

perfect world.

In reality, Teeter said, various stressors—especially disease—can significantly drain

energy reserves and rob birds of nutrients

they need to achieve optimal growth.

Stressors can also work together to have

a negative effect. "It's the combination

of stressors that have the most impact,"

he said.

Bigger impact with age

While minimizing stress as much as

possible is an important goal for broiler

producers, paying attention to the timing

of these stressors is also crucial, Teeter

said. "Early exposure to stress is, of course,

detrimental, but it has a much smaller

overall impact in terms of weight gain

or feed use," he said.

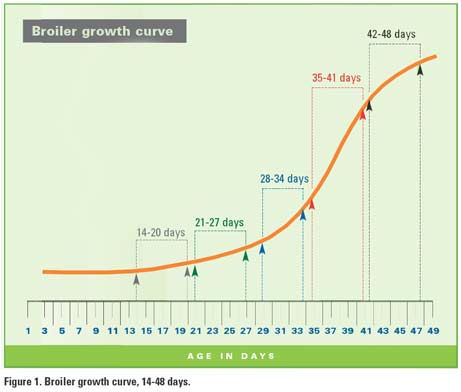

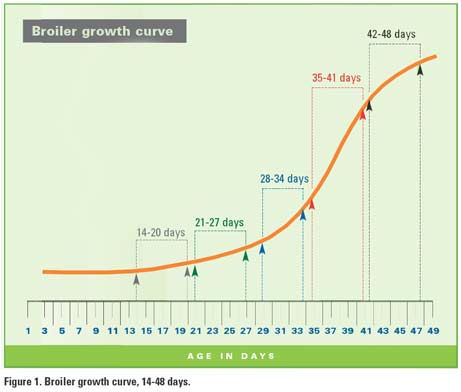

The growth curve for broilers accelerates

rapidly after about 27 days, Teeter

explained. "If the bird is hit with a

stressor before that 27-day mark, it has

time remaining to make up for any

performance it loses," he said. "But late

stressors that happen from 27 days

onward simply don't give the bird

enough time to recover lost growth."

For years Teeter and his colleagues have

been studying birds placed in high-tech

metabolic chambers that allow the

researchers to measure even subtle

changes in the birds' energy intake and

utilization. As part of that work, they

developed statistical models that reliably

predict metabolizable energy consumption

in disease-free birds.

Challenge of disease

But what about energy consumption in

birds challenged by disease?

According to Teeter, coccidiosis is one

of the most significant disease stressors

that commercial broilers face. Using tests

in his metabolic chambers, his team

contrasted healthy with infected birds in

terms of growth rate and final mass,

average daily gain (ADG), feed efficiency,

energy loss from waste excretion,

and energy use for maintaining bodily

functions.

In past work, Teeter's group confirmed

that coccidia—the parasitic organisms

that cause coccidiosis—do, indeed, have

a significant detrimental effect on all

those parameters. However, more recently

they have been digging more deeply into

how the timing of coccidia challenge

affects those measurements.

"Broilers don't grow in a strictly linear

way," Teeter reminded the audience of

veterinarians, nutritionists and production

managers. "Most of their growth takes

place after 27 days, the latter part of their

growth curve."

Based on his

findings, he thinks the timing of the

"coccidiosis insult" makes a significant

difference in how birds utilize energy

for growth.

Based on his

findings, he thinks the timing of the

"coccidiosis insult" makes a significant

difference in how birds utilize energy

for growth.

Teeter's group performed a study in which

they assigned a group of broilers to either

an experimental or control group. The

experimental group was challenged with

three common coccidia pathogens—Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina and

Eimeria maxima—and placed in the

metabolic chambers for 6 days to track

performance, body composition, metabolic

heat production, calorie expenditure and

calorie loss due to excretion. Control birds

were administered only a sterile solution.

After 6 days of collecting data in the

chamber, researchers euthanized and

necropsied the birds, ranking lesions for

severity using a standardized system.

Teeter reported that coccidia challenge

had a negative effect on performance of

all birds, with the highest lesion scores

correlating with poorest performance.

That was especially true in birds that

received a mixed challenge of at least

two species of coccidia.

More surprising, however, was that even

low lesion scores were associated with

a negative impact on performance,

especially as birds neared the end of their

growth curve.

Late coccidiosis exacts heaviest toll

To more fully assess the importance of

timing of coccidiosis challenge, Teeter's

group compared two groups of broilers—one reared in an environment that

provided a low level coccidia challenge

delivered by a live coccidiosis vaccine

(Coccivac-B); the other received

no challenge.

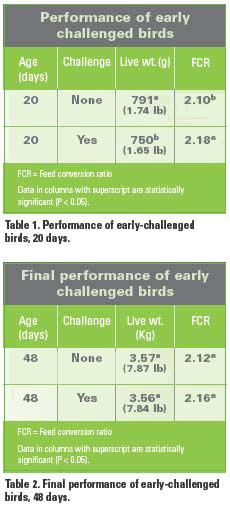

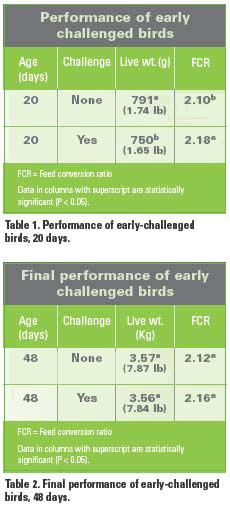

At 20 days of age, researchers tallied

performance numbers and necropsied

50% of the birds. The rest were reared for

the full grow-out period of 48 days while

researchers monitored their performance.

"In the group of birds necropsied at

20 days, microscopic lesion scores were

different from controls in every case,

even for this mild level of exposure,"

Teeter said.

Performance indicators such as live weight

and feed conversion also reflected some

negative effects of early cocci challenge.

However, Teeter emphasized, by 48 days

the birds had overcome that reduction in

performance—a process known as compensatory gain (Tables 1 and 2).

"At that point the average weight of the

birds was not different—about 3.56 to

3.57 kg (7.84 to 7.87 pounds) and the

feed-conversion rate was also the same as

controls." Overall, he said that the coccidia-

challenged birds regained all of their

body mass and there was no significant

difference in feed conversion between

them and the non-challenged controls.

Measuring lost growth

Teeter also told the audience about a

useful set of mathematical modeling

tools they've developed to track how and

when birds metabolize feedstuff—a

measurement he calls "metabolizable

energy consumption."

These models assume that birds are raised

in disease-free conditions. If birds expend more energy than what's predicted by

the disease-free model, it suggests that

energy is being lost—either as additional

energy needed for maintenance (e.g.,

generating extra body heat, mounting

immune responses, increased physical

activity) or possibly from decreased

digestibility of the ration itself or

perhaps extra energy lost in excreta.

He said many of his group's findings

confirm the importance of producers

guarding against late coccidia challenge.

"When we use these tools to look at

the data we've collected," he said, "there

is a constant that seems to emerge from

the numbers—that is, for each increase

in microscopic coccidiosis score, ADG

decreases approximately 1.5% of

body weight."

That means, he said, that for a 2-kg

(4.4-pound) bird with a lesion score of 1,

the loss in ADG would be expected to be

about 30 grams (0.066 pound) per day.

For a similar size bird with a lesion score

of 2, the loss doubles to about 60 grams

(0.132 pound) per day.

These mathematical tools also show that

feed efficiency suffers in the presence

of coccidiosis.

"For each increase in visual coccidiosis

score, feed efficiency decreases approximately

0.0084% per gram (0.002 pound)

of live weight," he said, noting that nearly

half of feed eaten by birds is consumed

during the final 2 weeks before processing.

"So even with a coccidiosis score of 1, the

impact on final feed conversion is going to

be enormous."

Field experience confirms lab results

Experience gained in real-world settings

lends credence to Teeter's findings about

the potentially devastating effects of late

cocci challenge.

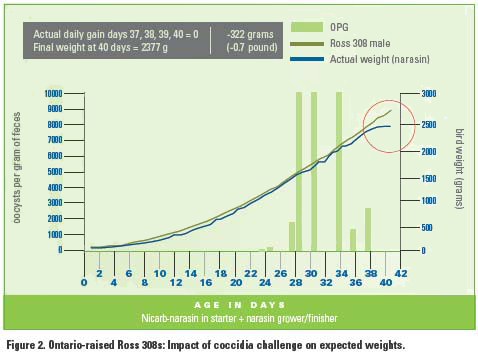

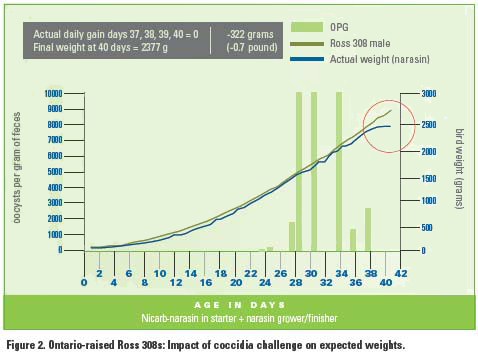

In one operation in Ontario, Canada, with

Ross 308 birds that were not vaccinated

against coccidiosis, very high oocyst

counts were noted around day 29, though

no symptoms of coccidiosis such as bloody

droppings were present.

When expected weights for the Ross

308 birds (as provided by the breeding

company) were plotted on a graph along

with the actual weight of the birds, a

significant loss of growth—culminating in

zero growth—was seen at day 39 onward

. Observers suspect some of

the loss in growth may have been due to

coexisting necrotic enteritis, though no

clinical evidence of that was seen.

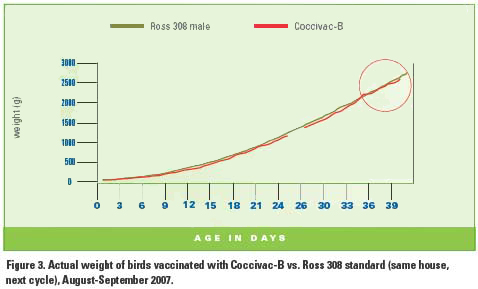

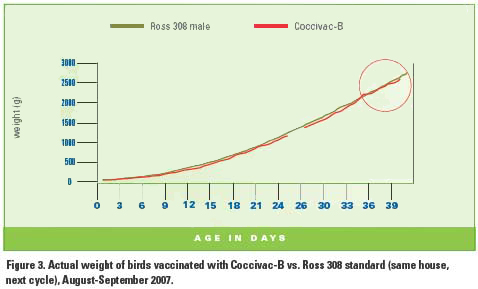

In later flocks the Canadian producer

decided to use a live coccidiosis vaccine

(Coccivac-B) to provide early cocci

challenge. The results were dramatic.

Late weight loss was avoided due

to earlier development of immunity

(Figure 3).

Such accumulating data, Teeter says, are

powerful. "I've been awe-struck at the

tremendous impact late-stage coccidiosis

has on performance."

He sums up, "It is critical for broiler

producers to make a routine analysis of

the timing and severity of coccidiosis

challenge because, if it happens early, the

birds have time to recover. If it happens

late, toward the end of the production

cycle, there's just not enough time for

them to recover, and even minor lesions

can cause huge losses."

Spring 2008

Regresar a North American Edition (#1)

Experience gained in real-world settings

lends credence to Teeter's findings about

the potentially devastating effects of late

cocci challenge.

Experience gained in real-world settings

lends credence to Teeter's findings about

the potentially devastating effects of late

cocci challenge.

In later flocks the Canadian producer

decided to use a live coccidiosis vaccine

(Coccivac-B) to provide early cocci

challenge. The results were dramatic.

Late weight loss was avoided due

to earlier development of immunity

(Figure 3).

In later flocks the Canadian producer

decided to use a live coccidiosis vaccine

(Coccivac-B) to provide early cocci

challenge. The results were dramatic.

Late weight loss was avoided due

to earlier development of immunity

(Figure 3).

Based on his

findings, he thinks the timing of the

"coccidiosis insult" makes a significant

difference in how birds utilize energy

for growth.

Based on his

findings, he thinks the timing of the

"coccidiosis insult" makes a significant

difference in how birds utilize energy

for growth.

© 2000 - 2021. Global Ag MediaNinguna parte de este sitio puede ser reproducida sin previa autorización.

© 2000 - 2021. Global Ag MediaNinguna parte de este sitio puede ser reproducida sin previa autorización.