Hofacre: 'Necrotic enteritis...a big performance issue':

"So we're not just talking about necrotic enteritis as a mortality issue. It's a big performance issue."

"So we're not just talking about necrotic enteritis as a mortality issue. It's a big performance issue."

DR. CHUCK HOFACRE

It's no secret that necrotic enteritis is

a big problem in poultry. The ubiquitous

disease, caused by the soil-borne

organism Clostridium perfringens, costs

the world's poultry producers some $2

billion every year or as much as 5 cents

per bird, according to published reports.

The difference today, specialists say, is

that there's more of it, thanks in part to

the declining use of antibiotic growth promoters

and in-feed anticoccidials, which

helped to manage the disease. Hoping to

gain more insights on the chronic bug,

researchers are also taking a second look

at control measures.

Dr. Chuck Hofacre—a professor and

director of clinical services at the

University of Georgia who's been looking

into the causes and cures of necrotic

enteritis (NE) for the past 10 years—said

that putting this new information to work

can help producers raise healthier and

more profitable birds.

Fewer AGPs, more necrotic enteritis

In his presentation, Hofacre began by

pointing out that until recently, necrotic

enteritis hadn't been that big a problem in

most conventional broiler operations. That's

partly because the antibiotic growth promoters

(AGPs) used in many flocks had an

added, albeit unintended, effect: they

helped control clostridium. Now that more

growers are bowing to consumer pressure

to get AGPs out of their poultry, necrotic

enteritis has been gaining a foothold.

Even when NE doesn't kill birds, it can

have a devastating effect on performance.

"If we don't do something to prevent

necrotic enteritis," said Hofacre, "we're

going to have less feed-efficient birds, and

we're going to have lower body weight

birds. So we're not just talking about

necrotic enteritis as a mortality issue. It's

also a big performance issue."

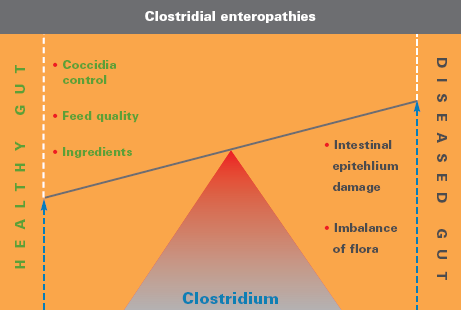

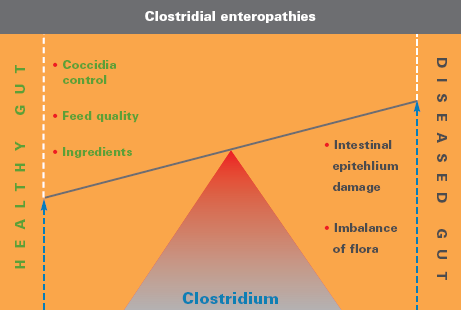

Figure 1.

Figure 1. A mix of "good" and "bad" bacteria in the intestinal tract of chickens can significantly impact necrotic enteritis and overall health of the birds.

One of the most important findings that's

come to light in recent research is that the

mix of both "good" and "bad" bacteria

in the intestinal tract of chickens has a

significant impact—not only on NE, but

also on birds' overall health (Figure 1). He

identified several ways to control that mix.

One is by paying close attention to the

composition and quality of foodstuffs.

Grains that contain a significant amount

of non-soluble fiber, such as wheat, barley

or oats, can predispose birds to NE.

Growers need to keep in mind, Hofacre

said, that some intestinal bacteria thrive

on certain foods, while others don't.

For example, in Canada, poultry growers

tend to rely on plentiful supplies of wheat

to grow their birds. Wheat contains high

levels of non-starch polysaccharides, biochemical

components that chickens can't

digest. Some types of intestinal bacteria,including C. perfringens, which produces

the toxin associated with NE—thrive on

polysaccharides.

Animal byproducts in feedstuffs can be

a predisposing factor, too. Research has

shown that some blended feeds that

contain fish or bone meal have thousands

of clostridium spores per gram. That means

broilers may be getting a heavy dose of

clostridia along with their food.

But, Hofacre points out, the economic

realities of running broiler operations often

make some give-and-take necessary when choosing feed. Readily available

and lower-cost ingredients sometimes

make more sense in the long run. "So

those farmers in Canada are not about

to stop using wheat," he said.

And there's no need to shun wheat, either,

he said. "These differences in the way

that feeds affect the intestinal flora can

be managed," Hofacre added. "Growers

just need to understand how all the

factors that influence necrotic enteritis

fit together."

For example, during periods of heavy

coccidia challenge, when the birds

have more stress on the gut, he urges

producers to consider cutting down

on ingredients in the feed that might

cause problems.

PCR: A useful tool

One tool that researchers have been

using recently to help unlock the mysteries

of intestinal health is polymerase chain

reaction (PCR) technology—"the same

technology the good guys use on TV's CSI to solve crimes," Hofacre said. With

PCR, poultry scientists can analyze the

content of chickens' intestines to find out

exactly what bacteria are there and in

what proportions.

For most of the life of a broiler, C. perfringens,

along with other non- toxic strains

of clostridium, rank second—behind

the bacterium lacto bacillus—in the

competition among gut microflora. One

of the reasons C. perfringens has such

a strong presence in the gut is that

the enzymes it produces feed on

endothelial mucous.

When the lining of the intestine is damaged,

even minimally, by irritation from a disease

organism, it produces mucous. Over the

eons that C. perfringens has evolved,

explained Hofacre, the bacterium learned

to essentially feed off the mucous. The

result is that clostridia grow faster, produce

more toxins, more damage and more

mucous, and the cycle just continues.

Maintaining a protective shield

What steps can broiler producers take

to break the cycle?

First and foremost, emphasized Hofacre,

producers need to begin thinking of the

microflora of the gut as a protective

shield that, if it contains a healthy mix of

organisms, can help protect the delicate

lining of the intestine from damage. A vital

component in controlling NE, therefore, is

to make sure the mix of microflora stays

tilted to the healthy types.

One way to do that, he said, is to supplement

the feed with natural products such

as organic acids, which help promote a

healthy balance of gut microflora.

Another is cleaning and disinfecting the

house between flocks. That's especially

true in operations that have a history of NE.

Still another is keeping the moisture content

in the litter down to a healthy level,

since increased moisture raises the risk

for NE.

Perhaps the key component in heading

off necrotic enteritis is the use of good

coccidiosis control, which makes the gut

less vulnerable.

"We've controlled coccidia with chemicals

and drugs, and we'll continue to do that,"

Hofacre said. But, once again acknowledging

mounting consumer pressure to cut

down on these feed additives in food

production, he added "if we're going to

produce a product without any antibiotics,

then we're going to have to look at other

ways to control coccidia."

Spring 2008

Regresar a North American Edition (#1)

Figure 1. A mix of "good" and "bad" bacteria in the intestinal tract of chickens can significantly impact necrotic enteritis and overall health of the birds.

Figure 1. A mix of "good" and "bad" bacteria in the intestinal tract of chickens can significantly impact necrotic enteritis and overall health of the birds.

© 2000 - 2021. Global Ag MediaNinguna parte de este sitio puede ser reproducida sin previa autorización.

© 2000 - 2021. Global Ag MediaNinguna parte de este sitio puede ser reproducida sin previa autorización.